Building a Simple User Interface - XML

OK, let's do the same thing, only this time the Android way (using XML).

The first advantage gained by going this route is that we can almost follow (or in my case copy) word-for-word the content of this Android tutorial. This is good because by knowing how to do something the Android way you'll be able to tap into a very large community of experienced Android developers.

For the sake of consistency, I'm going to write it up in my own words but you might be interested to give that a read (if you didn't the first time I mentioned it) so that at least you won't give me credit for something I didn't do.

Oh, also, before you read on, I recommend perusing this article from the API Guides on Layouts. It's basically a glorified advert for using XML, but you should still read it!

Create a Linear Layout

Instead of creating an instance of the LinearLayout class in the

onCreate method of our activity, we'll create it in an XML file, it will be compiled into a View resource and then we'll load it for our Activity.

Step 1 - Create the XML

At the top-level of your RubyMotion project you have a folder called resources. You can reference files here with the top-level constant R.

If we create a folder here called layout then we'd reference its contents as R::Layout.

So go ahead and copy+paste the following into a new XML file that I call first_layout.xml

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"

android:orientation="horizontal" >

</LinearLayout>

Speaking of typing . . .

This is the minimum required to get a basic layout going.

- Declare the XML version / encoding

- Create a root element (only 1, see this)

- Specify a width, height and orientation if its a

LinearLayout. We usedmatch_parenthere because our activity has only one view so it may as well take up the whole screen.

So yeah, XML isn't going to save your fingers, but it gives you easy access to a lot of attributes for styling widgets, some of which have no corresponding programmatic method.

Step 2 - Load the Resource

Now we just need to load the XML resource in the activity. In Java we reference the file as

R.layout.first_layout

we'd say that we are referencing the R class (Android's resource package) and the layout class within that.

In Ruby we do the same thing with modules and classes, so RubyMotion converts the Java way to a Ruby-like way (see the docs), meaning we chain together the namespace by :: and we capitalize package names R::Layout::First_layout. Yeah that looks a little weird, so if you like you can rename the XML to FirstLayout.xml.

Anyways, we load it like so:

class MainActivity < Android::App::Activity

def onCreate(savedInstanceState)

super

setContentView(R::Layout::First_layout)

end

end

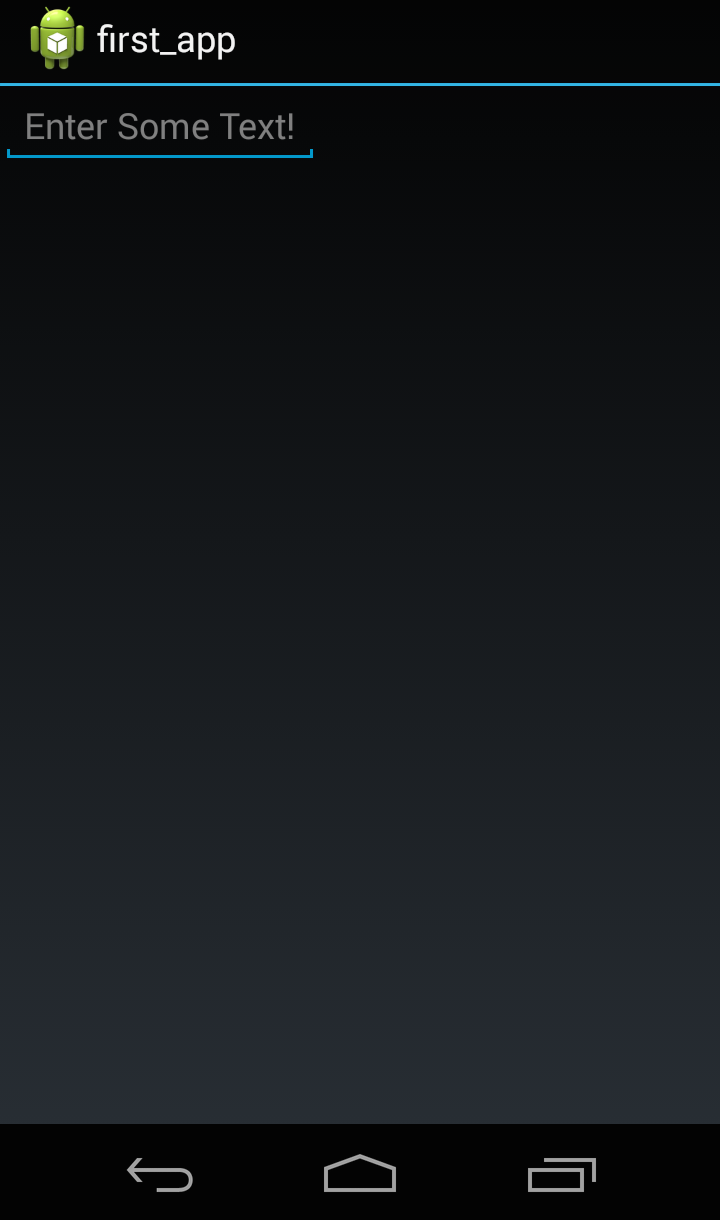

Add a Text Field

At its core, adding an EditText is as simple as

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"

android:orientation="horizontal" >

<EditText/>

</LinearLayout>

But of course some things are needed. For example if you attempt to compile the above you'll get an error saying the EditText needs a layout_width attribute. This is interesting because where we needed to jump through some hoops to access the layout_width of the EditText before, now it is an essential part of what an EditText is and is easily set:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"

android:orientation="horizontal" >

<EditText

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content" />

</LinearLayout>

XML ids

So that you can reference resources (such as your EditText) from other places in the code (either programmatically or from other pieces of XML) each item can / should have its own id like so:

<EditText android:id="@+id/edit_message"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content" />

The id syntax works like this: the @ symbol says I'm referencing a resource (@id in this case, we'll use a different resource @string in a moment) and the + symbol says "I'm creating a new resource". So in other words "@+id/edit_message" I'm creating a new resource id: edit_message and now you can refer to your EditText by this id.

When you create resources like this you really are adding to a HUGE pile of resources that are already made available by the R package. So that + sign isn't just for show!

Attributes and String Resources

Now, let's say we want to add a "hint" text for the EditText like we did in the previous lesson. Next to the setHint method in the docs is an attribute: android:hint. We use it like so:

<EditText android:id="@+id/edit_message"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:hint="Enter Some Text!" />

We could write the content of the hint here directly. But the Android way is to reference a string resource like this:

<EditText android:id="@+id/edit_message"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:hint="@string/edit_message" />

You create an @string resource by putting a new xml file in resources/values (you'll need to create the values directory) as strings.xml. Go ahead and copy+paste:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<resources>

<string name="edit_message">Enter Some Text!</string>

</resources>

Please take a minute to absorb that. The machinery read in that xml file and made the contents of a string resource with name 'edit_message' available to you as a variable. Very useful!

Here's a note from the developer trainings explaining the importance of doing strings this way:

For text in the user interface, always specify each string as a resource. String resources allow you to manage all UI text in a single location, which makes the text easier to find and update. Externalizing the strings also allows you to localize your app to different languages by providing alternative definitions for each string resource.

Before we move on to the button, I'd like to point out that this business about resources is important. There is a whole chunk of the guides dedicated to them!

For example, in the above, I put my strings.xml in the resources/values/ directory. Is that directory name special? What about the strings.xml filename? Does it have to be strings? The answers to basic questions like this (yes and no in that order) can be found here. As questions like these arise, don't ignore them! Go to the guides and read up!

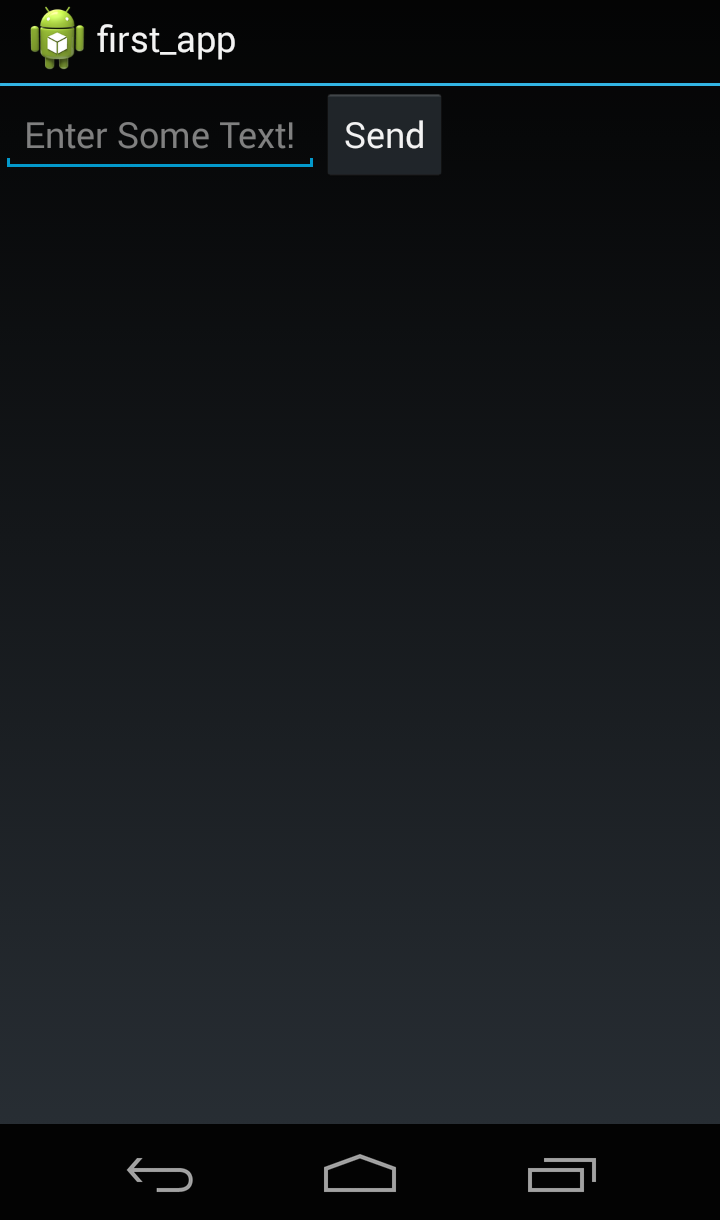

Add a Button

If you're starting to see the pattern then good! See if you can figure out how to add a button that says 'Send' using XML.

(Give it a try before you read on and see the answer).

If you're not seeing the pattern, here's how it's done:

<Button

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="@string/button_send" />

(+10pts if you used a string resource like above instead of adding the string directly!)

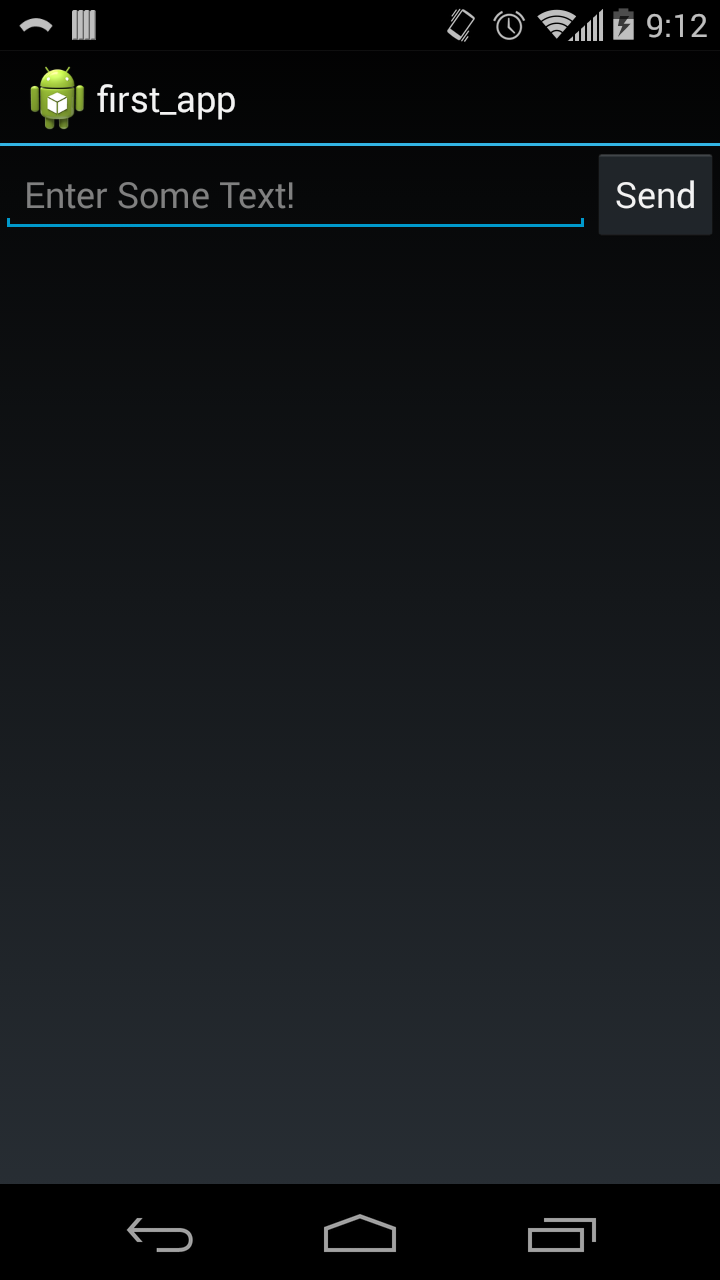

Adjusting Width via XML

In the last lesson I spent a lot of time talking about how to adjust the width of that EditText (some might say too much time). But in this lesson you can already see how to get the layout_width to match_parent so the only thing I need to mention is weight. And even then it's very simple:

<EditText android:id="@+id/edit_message"

android:layout_weight="1"

android:layout_width="0dp"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:hint="@string/edit_message" />

The only thing new here is the layout_width="0dp". Again, from the training:

Setting the width to zero improves layout performance because using "wrap_content" as the width requires the system to calculate a width that is ultimately irrelevant because the weight value requires another width calculation to fill the remaining space.

Conclusion

So that's it for an XML UI. Since this is the Android way it does simplify some things (such as size control), but at the end of the day no one should have to write XML by hand. That means this way is sluggish without 3rd party tools to do the heavy lifting for us.

For the final lesson in these "First App" tutorials, we'll learn how to start up a new activity. Since this can be done both programmatically and via XML we'll be looking at how this is done in both situations.